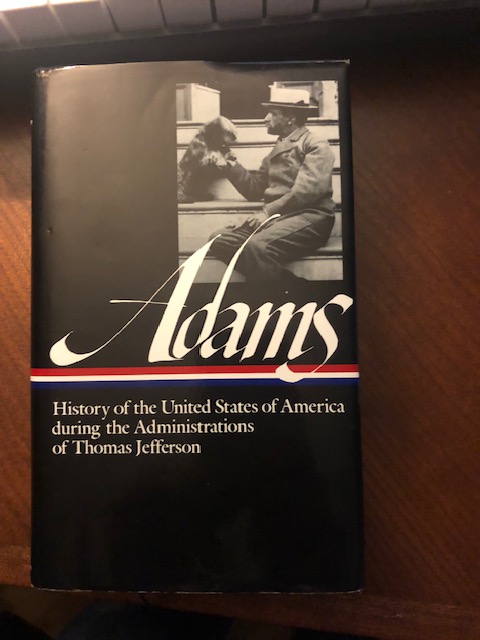

That’s my current reading project in the picture. Pretty good chance I will at some point abort, as it comes in at just over 1250 pages, and has a companion, History of the US During the Administrations of James Madison, which is also about 1250 pages. Someone trained in actuarial science could likely confirm that, at my current rate of progress, there’s a credible chance I wouldn’t finish the work even if I myself never decided to quit.

If, though, I had a bad diagnosis, I think I’d put down Henry Adams and take up someone else, maybe Elmore Leonard. Not that I’m torturing myself. I read in bed, and a lot of it acts as a soporific, but then there is too, for example, the moment when Thomas Jefferson, obviously a major figure in this immense work, first appears on stage:

According to the admitted standards of greatness, Jefferson was a great man. After all the deductions on which his enemies might choose to insist, his character could not be denied elevation, versatility, breadth, insight, and delicacy; but neither as a politician nor as a political philosopher did he seem at ease in the atmosphere which surrounded him. As a leader of democracy he appeared singularly out of place. As reserved as President Washington in the face of popular familiarities, he never showed himself in crowds. During the last thirty years of his life he was not seen in a Northern city, even during his Presidency; nor indeed was he seen at all except on horseback, or by his friends and visitors in his own house. With manners apparently popular and informal, he led a life of his own, and allowed few persons to share it. His tastes were for that day excessively refined. His instincts were those of a liberal European nobleman, like the Duc de Liancourt, and he built for himself at Monticello a chateau above contact with man. The rawness of political life was an incessant torture to him, and personal attacks made him keenly unhappy. His true delight was in an intellectual life of science and art. To read, write, speculate in new lines of thought, to keep abreast of the intellect of Europe, and to feed upon Homer and Horace, were pleasures more to his mind than any to be found in public assembly. He had some knowledge of mathematics, and a little acquaintance with classical art; but he fairly revelled in what he believed to be beautiful, and his writings often betrayed subtile feeling for artistic form,–a sure mark of intellectual sensuousness. He shrank from whatever was rough or coarse, and his yearning for sympathy was almost feminine. That such a man should have ventured upon the stormy ocean of politics was surprising, the more because he was no orator, and owed nothing to any magnetic influence of voice or person. Never effective in debate, for seventeen years before his Presidency he had not appeared in a legislative body except in the chair of the Senate. He felt a nervous horror for the contentiousness of such assemblies, and even among his own friends he sometimes abandoned for the moment his strongest convictions rather than support them by an effort of authority.

One wonders whether the realism of this portrait of an American saint, which only deepens as the narrative proceeds, owes anything to the bitter election of 1800, in which Jefferson prevailed over the author’s great-grandfather, John Adams. But, no, that seems not to be the case, as evidenced by Adams’s brisk dismissal, a few pages later, of the following contemporary “poetic” lines–

The weary statesman for repose hath fled

From halls of council to his negro’s shed;

Where, blest, he woos some black Aspasia’s grace,

And dreams of freedom in his slave’s embrace.

–which he calls the invention of a libeller. Not so fast, Henry!

Leave a comment